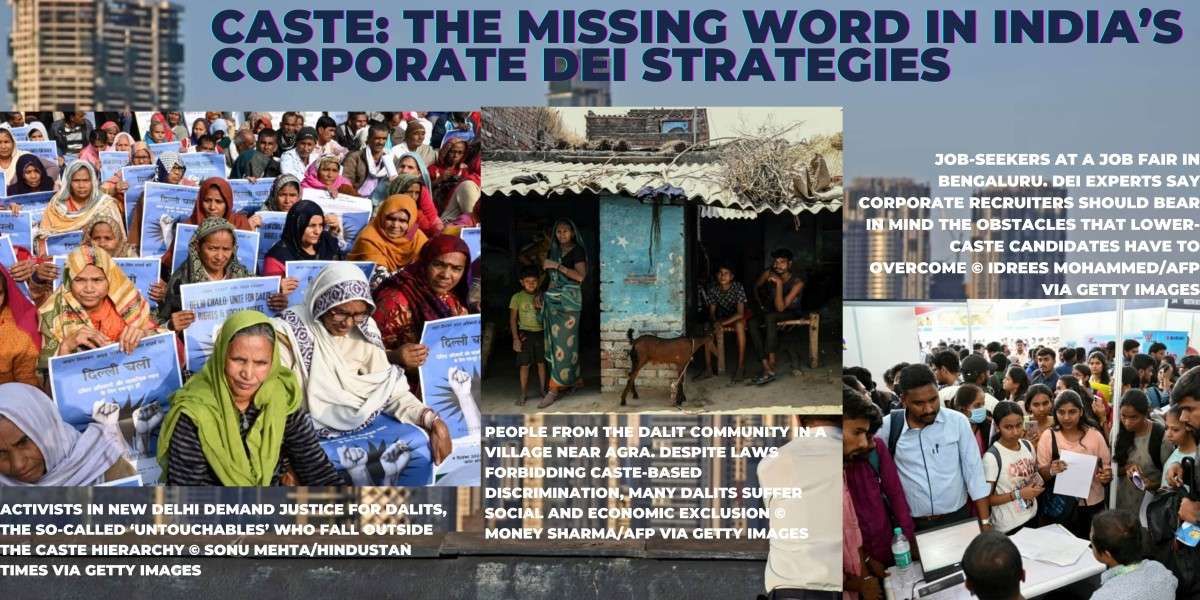

Caste: The Missing Word in India’s Corporate DEI Strategies

- Dignity Post

- 15-11-2024 09:31

Browse corporate India's Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) sections, and you’ll notice a glaring omission: “caste.” While terms like “gender,” “sexuality,” “physical ability,” and “race” dominate public-facing pages, caste—a system affecting hundreds of millions of Indians—barely gets a mention. Occasionally, it appears in downloadable documents such as codes of conduct, but it is often absent.

“It’s not surprising—most Indian companies shy away from discussing caste,” says Christina Dhanuja, a DEI-caste strategist based in Chennai. Caste, an ancient social hierarchy rooted in Hinduism, remains a sensitive topic, as addressing it involves confronting the privileges of upper castes and the historical implications of the country’s dominant religion.

Caste and Economic Inequality

India officially banned caste-based discrimination in 1947 and implemented quotas reserving 50% of government jobs and university seats for marginalized groups. However, these measures remain contentious, often sparking resentment among upper castes. Disparities persist despite hopes that economic growth and modernization will bridge the caste gap. A recent report by the World Inequality Lab, co-authored by economists like Thomas Piketty, highlights caste as a unique lens for viewing India’s economic inequality.

States like Telangana have initiated caste censuses to identify lagging communities, and opposition parties are pushing for a national caste census—a move the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party may need to consider given the demographic reality.

Corporate Blind Spots

While many companies claim to be “caste-blind,” experts argue that caste underpins almost all social and economic relationships. “Caste is everywhere,” says Meenakshi, a DEI consultant at Kelp, an HR firm in Chennai. Despite anti-discrimination laws, Dalits and lower-caste individuals remain underrepresented in white-collar jobs. Research shows that caste bias persists in hiring; for instance, candidates with high-caste surnames are more likely to get interview calls than their lower-caste counterparts with identical qualifications.

In a sector dominated by upper castes—who control over 55% of the country’s wealth—progressive corporate DEI policies have largely ignored caste. Companies often follow Western DEI frameworks, prioritizing gender and racial diversity while sidelining caste issues.

The Case for Inclusion

Dhanuja and other DEI advocates argue for an “Indianized” DEI model that incorporates caste, asserting that inclusive workplaces unlock broader talent pools and foster innovation. Studies support this: diverse teams outperform homogenous ones. However, change is slow. Few companies track caste data, and many lower-caste employees feel compelled to hide their identities to avoid discrimination.

To address caste inequity, experts propose steps such as conducting workplace surveys, raising caste awareness through training, and revising hiring practices to recognize skills beyond traditional merit markers like fluency in English. Some suggest companies should go further, explicitly inviting marginalized candidates to apply and setting hiring targets.

Challenges and Risks

Despite these recommendations, resistance remains. Critics warn of potential backlash, including false discrimination claims and pushback from upper-caste employees. “Any sudden shift could provoke strong negative reactions,” cautions Pratap Tambe, a manager at Tata Consultancy Services.

Yet, Dhanuja believes companies that ignore caste risk legal and reputational damage as public awareness grows. “Adapt or face consequences,” she warns, emphasizing that embracing caste diversity is not just a moral imperative but a business necessity.

Conversation