South Asian Dalit journalists to celebrate Jan 31 as International Dalit Media Day

- Dignity Post

- 30-07-2023 11:17

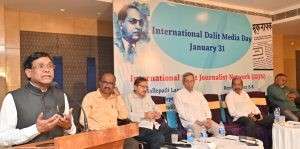

International Dalit Media Day was attended by Dr Raj Shekhar Vundru,

Biru Nepali

KATHMANDU: Dalit journalists of South Asia have announced to celebrate January 31 as International Dalit Media Day every year.

Through its virtual meeting held on Tuesday, the International Dalit Journalists Network (IDJN) announced to celebrate the day resembling the day when Dr Bhim Rao Ambedkar had started journalism to end discrimination against the Dalit community. On January 31, 1920, Dr Ambedkar started a fortnightly newspaper ‘Mooknayak’. In memory of the day, the IDJN has decided to officially recognize the day.

While announcing the day, the chairperson of the IDJN Mallepali Laxmaiah claimed that the media were biased on the issues of Dalits.

Saying that media is the mirror of society and a strong weapon, he said that he attempted to bring all the Dalit journalists of the world together to ensure the rights of the Dalit community and make the states responsible.

He also said the network will coordinate with all the rights activists, human rights fighters, journalists and responsible sections of the society together to the issues of Dalits. Laxmaiah had said this while welcoming all the guests to the function.

He also said the network will coordinate with all the rights activists, human rights fighters, journalists and responsible sections of the society together to the issues of Dalits. Laxmaiah had said this while welcoming all the guests to the function.

General secretary of the IDJN Rem Bahadur Bishwokarma said the network decided to declare the International Dalit Media Day just to respect the contribution of the Dr. Ambedkar-initiated media for the liberation of Dalits. He said the media can play a strong role in the liberation of Dalits and can also play a very important role to make society more responsible besides the transformation of the society.

Bishwokarma said the IDJN will celebrate January 31 as International Dalit Media Day with much fanfare every year.

The function organized to announce the International Dalit Media Day was attended by Dr Raj Shekhar Vundru, additional chief secretary of Haryana State; Milind Awasarmol, Board of Director of the Ambedkar International Mission; DB Sagar Bishwokarma, chair of the Dalit Rights International Commission; Bina Pallikal, chair Asian Dalit Rights Forum; Arun Khote of Justice News Lucknow India among others.

The function organized to announce the International Dalit Media Day was attended by Dr Raj Shekhar Vundru, additional chief secretary of Haryana State; Milind Awasarmol, Board of Director of the Ambedkar International Mission; DB Sagar Bishwokarma, chair of the Dalit Rights International Commission; Bina Pallikal, chair Asian Dalit Rights Forum; Arun Khote of Justice News Lucknow India among others.

Ambedkar’s ‘Mooknayak’ was published for three years and later he initiated three other newspapers as well–namely Bahiskrit Bharat (1927-1929); Janata (1930-1956) and Prabuddha Bharat (1956). Among them, he was directly involved in the editorial management of Bahiskrit Bharat besides Mooknayak

November polls fail to ensure fair representation of Dalits

The representation of Dalit community in the newly elected legislature—5.81 percent— is the lowest since the 2008 Constituent Assembly. Post Illustration

Kathmandu

The current Dalit representation in the legislature is the lowest since the 2008 Constituent Assembly. In 2017, three Dalits were directly elected while 16 came from the proportional representation category.

This time, however, only Chhabilal Bishwakarma of CPN-UML has been directly elected from Rupandehi-1. And a total of 15 Dalit candidates have been picked for the House of Representatives under the proportional representation category.

The scenario at the provincial assemblies is similar.

Only three Dalit leaders have made it to the provincial assemblies directly this time, down from four in the 2017 provincial elections. As many as 28 Dalit candidates have been picked to the provincial assemblies under the PR category. The number was 29 in 2017.

Observers said since the political parties decided to provide tickets to only a few Dalit leaders under the FPTP system, the community’s poor representation in legislatures was a foregone conclusion.

Pradip Pariyar, the executive chairperson of the Samata Foundation, an NGO working towards social justice, said the leaders of the old parties have been defying the constitution’s spirit to ensure proportional inclusion.

While providing tickets for direct elections, he added, “The political parties blatantly ignored the Dalits.”

JB Bishwokarma, a researcher and Dalit rights activist, argues along the same line. He said political parties should field Dalit candidates for FPTP seats and give them the chance to lead electioneering as leaders of their constituencies. “Unfortunately, that could not happen,” he said.

“Directly elected candidates are deemed more powerful and their ouster from the parties is not easy,” added Bishwokarma. “With the heat of the movement that ensured the proportional representation system waning, the parties have also been gradually ignoring the Dalits.”

The three major parties—the Nepali Congress, the UML, the CPN (Maoist Centre) and the CPN (Unified Socialist)—fielded only a paltry number of candidates from the Dalit community under FPTP system. The Nepali Congress did not field a single Dalit candidate. The Maoist Centre had two—Anjana Bishankhe from Kathmandu-10 and Maheshwar Gahatraj from Banke-1—while the UML fielded its secretary Chhabilal Bishwakarma in Rupandehi-1 and Chakra Prasad Snehi in Dadeldhura for the federal polls.

And even the new forces appeared no different than the traditional parties, said Rita Pariyar, a Dalit rights activist. “The new forces also did not bother to proportionally field the Dalit candidates under the first-past-the-post system. Instead, they chose a proportional representation category to elect Dalits,” she said. “New parties also don’t differ from the old ones as their office bearers have failed to incorporate Dalits based on the principle of proportional inclusion.”

In the recently-concluded polls, she added, even though very few Dalit independent aspirants contested, they could not secure victories given their weak economic background. Analysts have been saying Nepal’s elections are getting increasingly expensive, with candidates openly admitting they spend way more than the expenditure ceiling set by the Election Commission.

Another strain in the Dalit’s continued marginalization is that the Dalit leaders in parties and the elected lawmakers from the community often remain silent about their community’s poor representation, leading to a vicious cycle of their ostracisation in elections, say activists.

“The situation is worsening as Dalit lawmakers and leaders have not been accountable to their voters and have not raised their voices to ensure fair representation of Dalits in the legislature,” Pariyar, from the Samata Foundation, said.

Rita Pariyar, the Dalit Rights activist, said, “Elected Dalit lawmakers—most often the trusted lieutenants of top leaders—never stand against the party’s leadership to speak up for fair Dalits’ political representation.”

Problems also lie in legal provisions, according to observers.

Unlike for women’s representation, there lacks a mandatory provision that ensures population-based inclusive Dalit representation, said Pariyar, the executive chairperson of Samata Foundation.

He also sees the need to amend the Election Act, as it mentions the inclusion principle without stating that it should be based on population. “A compulsory legal provision is as necessary as the 33 percent provision for women,” he said.

Bishwokarma, meanwhile, said allocating seats to Khas-Arya in a reservation is itself faulty. According to him, the problem of proportional representation and reservation surfaced since the parties allocated certain seats to Khas-Arya—the dominant ethnic group.

“Proportional representation should be meant for the marginalized groups. But the concept has been overshadowed by the allocation of seats to Khas-Arya,” Bishwokarma told the Post. “Until this provision is rectified, marginalized groups like Dalits won’t be fairly represented.”

Nishan Khatiwada

Nishan Khatiwada is a reporter covering national politics for The Kathmandu Post. Before joining the Post, he worked for The Annapurna Express and Nepal Live Today.

Soruce: Kathmandupost

.jpg)

Conversation